Psychoneuroimmunology:

The Science Connecting Body and Mind

Published by SHAMIR -

www.borhatorah.org

Yakir Kaufman, MD

The Torah gave the world an understanding of the reciprocal

connections between body and soul. Until recently, many scientists rejected

the concept that psychological factors and well-being can affect health and

disease. In part, this may been caused by a lack of technological tools to

prove these links. During the last decade, new methods and findings in

neuroscience, neuroimaging, and molecular biology have discovered

connections between emotions and disease, between the brain and the immune

system, the mind and the body. Science and medicine are beginning to become

aware of this interplay. The

psycho-neuro-immunology

(PNI) revolution uplifts science from a mechanistic, dualistic,

reductionistic Descartian view of the human state to a more integrative

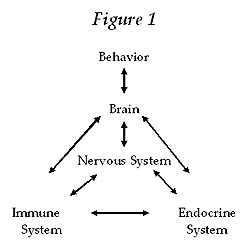

perception of the complexity and beauty of human existence. PNI deals with

the interactions among the mind, human behavior, the nervous system, the

immune system, and the endocrine system. Understanding these complex

interactions is essential for gaining a better understanding on how to

maintain health and to prevent and treat disease. PNI guides science to the

holistic view of body and soul interaction found in the Torah.

Yakir

Kaufman was born in Haifa and received his MD from the Hebrew

University Hadassah Faculty

of Medicine in 1994. In 1995 he become a resident doctor at the department

of neurology of the Hadassah University Hospital in Jerusalem. Dr. Kaufman

is a member of the Israeli Neurological Society and a junior member of the

American Academy of Neurology. With his wife and children, he is currently

in Toronto,

Canada, where he has been appointed a Fellow in the Behavioural Neurology

Program at the Baycrest Centre for Geriatric Care and the Rotman Institute.

His areas of research include psychoneuroimmunology and the link between

spirituality and health.

Mind-Body Unity: Science Is Catching Up with the Torah

The Torah

gave the world an understanding of the reciprocal connections between body

and soul. Genesis describes the creation of Adam as the implant of a

heavenly soul into an earthly body. Throughout the Torah the human

interaction between heavenly soul and animal body is an overriding theme.

This interaction is a cornerstone of the Torah perception of life.

Moses

Maimonides, the great Torah authority and physician, states in the third

chapter of his Regime of Health that his

medical system is based on the Torah concept of a �healthy soul in a healthy

body.�1 Maimonides expanded the Latin

aphorism of �a healthy mind in a healthy body.� Whereas Greek and Roman

medicine, as formulated by Galen, tried to treat the psyche as an isolated

system in cases of mental illness, Maimonides emphasized the necessity of

treating the spiritual aspect of every condition of every patient. He

understood that the physical well-being of a person is dependent on mental

well-being, and reciprocally, that mental well-being is dependent on

physical well-being. Furthermore, in the

Mishneh Torah,

Hilkhot Deot

4:1 Maimonides states that health is necessary in order to know G-d,

which is the highest purpose in life.

Throughout

the generations, similar concepts have been expressed by numerous Torah

commentators. In the past century, the Baal

Shem Tov and his hasidic followers emphasized

and revitalized this approach. The Maggid of Mazritch says, �A small hole in

the body is a big hole in the soul.�

In our

generation, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, wrote

to a conference of Torah observant physicians in New York in 1992, �physical

health depends upon the health of the nefesh

(soul)�the more healthy the nefesh is, the more it can guide the body to

mend its deficiencies� (Igrot Kodesh, volume

11, page 202).

Science and

medicine are beginning to awaken from a long unawareness concerning the

interplay between bodily factors and the mind and soul. In this sense, we

are lucky to be living in an exciting era, when the discipline of psycho-neuro-immunology

(PNI) is pioneering a revolution in elevating medicine from a mechanistic,

dualistic Descartian perception of the human condition to a new paradigm

embracing the complexity and beauty of human existence.

The old

reductionistic perception of the human being as the sum of many separate

biological systems is rooted in ancient Greek philosophy. The difficulty of

Western medicine in effectively treating many disease states, especially

chronic diseases, may be related to this narrow, non-integrative concept.

This attitude also incurs dissatisfaction from health service clients.

Patients feel they are looked upon by ultra-specialists as a compilation of

systems and not as an integrated human being.

In contrast

to the view that body systems function separately, technological development

in neuroimaging and molecular biology show that systems continuously

interact among themselves. Understanding these complex interactions is

essential for gaining a better perception on how to maintain health and

prevent and treat disease.2 This perception

may lead to the remodeling health-care.

New

and Ancient

Today�s

exponential growth in technology has allowed us to perceive and understand

the human body and brain as we have never done before. We can now �see� the

brain while it is engaged in the most delicate tasks. Technological

breakthroughs in neuroimaging, such as positron emission tomography (PET),

functional magnetic resonance (FMRI), and single photon emission

computerized tomography (SPECT), give us a first-time opportunity to

pinpoint areas of the brain that are responsible for the generation of

emotions, thoughts, and even higher abilities of the mind, such as

meditation and prayer.3, 4

Another

area of technological advancement that has boosted the understanding of the

connection between body and mind is molecular biology. Molecular biology has

given us the opportunity to track down minute quantities of substances

traveling through the human body and interacting with different systems of

the body. Of great significance are the molecules found interacting in the

brain, especially the limbic system responsible for our emotions, with other

bodily systems. The increasing ability to track the pathways of minute

amounts of molecules and monitor their effect on different systems has

enhanced our knowledge of how mental, emotional, or spiritual changes can

alter the molecular profile of the immune or hormonal system and thus affect

the body.5,6

Today, PNI

through molecular biology techniques provides evidence that

behavioral/psychological factors�primarily stress�can impair immunological

reactivity.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Conversely,

studies in PNI have demonstrated that reduction of stress can enhance immune

function in its task of protecting the body from infections, cancer, and

other disease states.12, 13,

14, 15, 16, 17, 18

Hence, as

more interactions between bodily systems are being discovered, science

better understands how changes in a person�s mental, emotional, or spiritual

state can change the molecular profile of his or her immune or hormonal

system, and thus affect the body.

Thus,

science today is approaching the Torah understanding that state of mind

affects physical health and disease.

Torah, PNI, and the Definition of Health

You will then serve G-d your L-rd, and he will bless your bread and your

water. I will remove sickness from among you�. I will make you live out full

lives. (Exodus 23: 25-26)

The ancient

but vital Torah concept of health expressed by Maimonides as a �healthy soul

in a healthy body� has been recognized by science only in the last century.

According to the modern definition of health, as defined by the World Health

Organization:

Health is a complete state of physical, social, and mental well-being and

the mere absence of disease or infirmity.19

�Mental

well-being� means both psychological and spiritual well-being. Health by

this definition is considered primarily an outcome of a person�s state of

well-being. Spiritual well-being is an important component of general

well-being.20 Whereas a deterioration of

well-being may bring disease, enhancement of well-being may prevent disease

or augment cure. Thus, the concept of the mind-body relationship as defined

in the Torah and rediscovered by PNI is embedded in the current definition

of health.

Stress and Disease

Psychoneuroimmunology deals

with the interactions among the mind, behavior, the nervous system, the

immune system, and the endocrine system.

One of the foci of PNI is the study of the stress phenomenon and its harmful

influence on the body, resulting in disease. Chronic stress, and its ill

effects is an example of the connection between body and mind. The cause of

disease is multi-factorial. It has been established that chronic stress is a

risk factor in the leading causes of morbidity and mortality. Chronic stress

has been shown to be a risk factor in heart disease, stroke, cancer,21,

22, 23 infection, 24, 25, 26 wound

healing,27 autoimmune disease,28,

29 depression,30, 31, 32

infertility,33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 pain,

and many other disease states.

Stress has

many definitions. A relevant one for our discussion is that stress is an

extraordinary demand on physiological and psychological defenses and

adaptation mechanisms with concomitant neuro-immuno-endocrine responses.

Stress

elicits a �fight or flight� (Hans Selye) reaction. This reaction is

essential in animals and humans for survival, particularly when encountered

by danger. The confronted organism can quickly recruit tremendous energy to

overcome danger either by fighting or fleeing the source of danger.

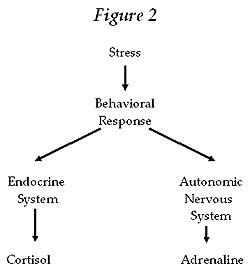

The stress

response mechanism is manifested in two major pathways (see Figure 2).

First, the endocrine pathway causes secretion of several stress hormones,

including CRH, ACTH, and cortisol. Cortisol has a potent, wide range effect

on many organs. After being secreted, it is distributed throughout the body

via the bloodstream. It enters the cells and affects the DNA within the

cellular nucleus, thus changing the functioning of the cells, organs, and

bodily systems.

The

second pathway is the autonomic pathway, involving activation of the

sympathetic nervous system that stimulates the adrenal gland to secrete

adrenaline. Adrenaline, like cortisol, has a large array of effects on

several systems.

The

significant changes following stress, although favorable on the short term,

have a high cost when repeatedly activated on the long run (i.e., chronic

stress). The stress response weakens the immune system�s ability to resist

disease. Thus, stress exposes us to reduced resistance. An ever-increasing

scientific database reveals that chronic stress is a risk factor for many

disease processes. Various studies indicate that stress events or breakdown

of psychological defenses are related to the onset of allergic, autoimmune,

infectious, neoplastic, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and other

illnesses. Other studies tie stress with myocardial infarctions (heart

attacks), stroke, cancer, hypertension, diabetes, arthritis, infertility,

depression, obesity, and many more problems. The first three illnesses

listed above are the main cause of morbidity and mortality in Western

societies today. This means that stress, by causing a �negative� mind-body

interaction, is a significant factor in morbidity and mortality.

The cause

of disease is multi-factorial. Why is it that while individuals within a

group of people (e.g., a family) may have a common genetic tendency to

develop a disease, only some of them will actually develop the illness while

others won�t? And why is it that virulent bacteria can be found in certain

people, of whom only a few will actually become infected and sick? These two

examples show us that diseases are caused by factors other than just a

certain genetic background or the mere presence of an infective agent (e.g.,

bacteria or virus). The decline of immune function through stress may be

responsible for the ability of the bacteria to cause infection or of a

genetic trait to become expressed as an actual disease.

Stress and Health: A Two-Way Street

Rebbe Nahman

of Breslov said, �If you believe you can damage, then believe you can mend.�

Studies

have repeatedly demonstrated that stress reduction can boost the immune

system, enhance well-being, and reduce morbidity and mortality risk.

Rebbe Nahman�s

counsel that we can mend as well as damage ourselves is paralleled in the

functioning of the stress mechanism. Amazingly, the same mind-body mechanism

that causes disease can work in the reverse direction and enhance health.

Numerous studies have shown that stress reduction and the enhancement of

well-being can boost the immune system and prevent disease. This means that

the same physiological mechanism connecting body and mind can work both

ways. The same mechanism can either cause disease through chronic stress or

reverse its harmful effects through reducing stress and augmenting

well-being.

We can

better appreciate this two-way process by acknowledging the placebo

phenomenon. A placebo drug is a substance that has no pharmaceutical impact

but nonetheless may actually cause a desired effect quite like that of a

�real� drug. Most drugs have been approved for use through a process proving

that its �sister� placebo drug actually had an effect. During the process of

developing new drugs the placebo effect becomes a �problem� because there

may not be a significant difference between the clinical effect of the

�real� drug and that of the placebo. Some scientists argue that certain

medications (e.g., anti-depressants) are effective mainly because of their

placebo effect.

What

underlies the placebo phenomenon? How can a mere �nothing� pill cure? The

placebo phenomenon seems to reveal the power of suggestion. Is it a trigger

for the mind to actualize an internal potential mechanism to cure the body?

Does it show an intrinsic ability of the mind to heal the body? The placebo

is an example of how it is possible for the mind to initiate a curing

process from within. The placebo phenomenon is an extraordinary illustration

of the therapeutic potential of the mind-body relationship when directed in

a constructive direction. With the right set of mind a person can improve

his or her physical condition. Numerous studies have shown this. Reduction

of stress through a wide range of strategies and techniques can reduce

morbidity and enhance the immune function to provide protection from

disease.

Is

Modern Medicine Targeted to Enhance Health?

The big

question is: If health is an outcome of well-being, then shouldn�t the

primary goal of any health system be the enhancement of well-being? Wouldn�t

a preventive medical policy through enhancement of physical, social, and

mental well-being be cost-effective? Is modern medicine inducing well-being?

And if not, why not? Many modern medicine patients feel that their

well-being decreases after an encounter with medical services.

There seems

to be an unwritten, silent agreement between patients and physicians saying:

When the patient comes to the physician with a complaint of a symptom, the

physician gives the patient a drug or surgery to relieve the symptom.

Although this relative relief of the symptom has its benefit, it does not

address the true underlying process that caused the disease to surface.

Studies have shown that certain medications that improved laboratory test

results in certain patients are liable to reduce well-being and on the whole

diminish health outcomes.39, 40

Modern

medical research has a tremendous mass of data on how to prevent disease and

to enhance health. Much more could be done to enhance well-being and prevent

disease (primary and secondary prevention). We lag behind in educating the

public about risk factors such as stress and its adverse effects. The public

should know that stressful lifestyles may be risk factors for disease.

Contemporary medicine is not primarily focused on preventing disease but on

treating disease after it has appeared. This focus makes the treatment more

costly and incomplete. Western health policy is building the proverbial

hospital under a broken bridge instead of fixing the bridge.

The West

could learn from China. In the past, the Chinese government paid subsidies

to health professionals if the community for which they were medically

responsible was physically well. This economic incentive actively enhanced

preventive medicine. In our society, physicians are usually financially

rewarded if they have more patients (and sometimes rewarded if they treat

their patients with more drugs and surgical procedures). This causes a

reversed incentive. Physicians today have a �heroic� role to save patients

suffering from life-threatening maladies. Preventive care to avoid disease

in the first place is considered much less heroic. It is also less

financially rewarding.

How

to Reduce Stress and Enhance Health

What is the

best, most long-lasting way to reduce stress and thus to enhance health? It

is clear that any symptomatic or superficial solution will be short-acting

and will have side effects (such as those given by anxiolytic drugs and

benzodiazepines).

When new

findings concerning the mind-body connection are acknowledged, then we may

conclude that the most profound way to reduce stress is through changing our

state of mind. To do this calls for deep, thorough, long-term introspective

work. It takes serious and consistent effort to change a state of mind that

has produced stress for many years into a different state of mind, but it is

possible to succeed.

Of course,

appropriate guidance is needed to go through such a complex, profound but

gradual change. If the mind is in constant turmoil and internal conflict,

the body also will not be at peace, and disease might eventually appear. If

anxiety, sadness, anger, dissatisfaction persist, these eventually will take

their toll on the immune, nervous, and endocrine (hormonal) systems and

bring about either mental or physical disease.

A profound

solution for this common situation is a conscious continuous learning

process of how to restore psychological, social, and spiritual well-being.

It is possible to learn how to restore long-lasting and true inner peace and

happiness. It takes dedication and time, but it�s definitely worth the

while. The body will benefit from this mindful effort. Our Talmud sages

said, �As the effort, so is the reward.�

When the

Maggid of Mazritch says, �A small hole in the body is a big hole in the

soul,� he is teaching us that to mend the body, we must first mend the soul.

Health comes about through a continuous quest to improve psychological and

spiritual well-being.

New

Model for Health Care

Healthcare

systems and physicians can easily integrate these new understandings in

their practice. Actually, good medicine based on mind-body interactions is

cost-effective and can save society tremendous unnecessary expenses. Public

money is wasted by building hospitals under broken bridges. A society that

places top priority on enhancing the well-being of its population, rather

than on waging technological wars against advanced stages of disease, can

dramatically cut its medical budget and create a healthier society.

Physicians

and other health professionals should discuss issues of well-being with

their patients. By both assessing well-being and stress factors in the

clients and prescribing therapies and strategies to reduce stress, doctors

can enhance the physical, social, psychological, and spiritual well-being of

their clients. Physical and mental disease can be prevented.

From

Treating Symptoms to Achieving Health: Where Mind and Matter Meet

If we

acknowledge the evidence showing the connection between mind and body, we

can then understand that inner stress, turmoil, or conflict is the source of

many maladies. Therefore, only by addressing these issues can the healing

process be complete. Only then is the solution a profound cure and not

merely symptomatic or superficial temporary measures. This more inclusive

approach demands the active participation of the patient. The therapist can

offer guidance, but it�s the patient who does the work (in contrast to

surgery or medication, where the patient is more passive).

As Jews we

have the merit and obligation to bring the light of G-d and the Torah down

into every aspect of this world. The Torah guides every aspect of our

lives�action, ethics, and morals. If we dwell deeply in the Torah, we can

find guidance for our search for a better health care system and optimize

our medical practice and our own well-being and health. We must take

advantage of the great opportunity brought by the new profound scientific

understanding of the physiology of mind-body interactions to remodel our

practice of medicine. The advancement in scientific understanding, aided by

the enormous progress made in medical technology, brings science closer to

the Torah paradigm of the connection between mind and body. The reciprocal

mind-body connection is the core of physical, social, psychological, and

spiritual well-being in health.

There is a

long called for need for quality medical professionals who have a complex

integrative understanding of mind-body interactions. There is a need for

healthcare workers dedicated to enhancing the well-being of their clients. A

responsible medical system can guide the individual and society to physical,

social, psychological, and spiritual well-being.

Part Two will discuss spiritual well-being and health.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Genesis & The Big Bang Theory by

Dr. Gerald Schroeder from

AishAudio.com

Genesis & The Big Bang Theory by

Dr. Gerald Schroeder from

AishAudio.com

Scientific Data Supporting Creation

by

Mr. Harold Gans

from AishAudio.com

Scientific Data Supporting Creation

by

Mr. Harold Gans

from AishAudio.com

Signature of God

by

Mr. Harold Gans

from AishAudio.com

Signature of God

by

Mr. Harold Gans

from AishAudio.com

The Fine

Tuning of the Universe

The Fine

Tuning of the Universe

The Moral

Approach to God's Existence

The Moral

Approach to God's Existence

The

Theological implications of Modern Cosmology

The

Theological implications of Modern Cosmology

Nature Reveals

Design

Nature Reveals

Design

Search For

Truth

Search For

Truth

Science

Quotes

Science

Quotes

Neurology and The Soul

Neurology and The Soul

The Cohanim / DNA Connection

The Cohanim / DNA Connection

The

Anthropic Principle

The

Anthropic Principle

Notes

1

Maimonides, Regimen of Health (1198) chapter 3.

See Fred Rosner, Medical Encyclopedia of Moses

Maimonides (Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, 1998) item �Psychosomatic

Medicine� pp. 183-184.

2

E.M. Sternberg, �Does Stress Make You Sick and Belief Make You Well? The

Science Connecting Body and Mind� in Ann NY Acad Sci

(vol. 917, 2000) pp. 1-3.

3

A.B. Newberg and J. Iversen, �The Neural Basis of the Complex Mental Task of

Meditation: Neurotransmitter and Neurochemical Considerations� in

Med Hypotheses (vol. 61, 2003) pp. 282-291.

4

A. Newberg, A. Alavi, M. Baime, M. Pourdehnad, J. Santanna, E. d�Aquili,

�The Measurement of Regional Cerebral Blood Flow during the Complex

Cognitive Task of Meditation: A Preliminary SPECT Study� in

Psychiatry Res (vol. 106, 2001) pp. 113-122.

5

J.K. Kiecolt-Glaser, L. McGuire, T.F. Robles, and R. Glaser,

�Psychoneuroimmunology and Psychosomatic Medicine: Back to the Future� in

Psychosom Med (vol. 64:1, 2002) pp. 15-28.

6

J.K. Kiecolt-Glaser and R. Glaser, �Psychoneuroimmunology and Health

Consequences: Data and Shared Mechanisms� in Psychosom

Med (vol. 57:3, 1995) pp. 269-274.

7

J.K. Kiecolt-Glaser, L. McGuire, T.F. Robles, and R. Glaser,

�Psychoneuroimmunology and Psychosomatic Medicine: Back to the Future� in

Psychosom Med (vol. 64:1, 2002) pp. 15-28.

8

W.B. Malarkey, J.K. Kiecolt-Glaser, D. Pearl, and R. Glaser, �Hostile

Behavior during Marital Conflict Alters Pituitary and Adrenal Hormones� in

Psychosom Med

(vol. 56:1, 1994) pp. 41-51.

9

J.K.

Kiecolt-Glaser, J.T. Cacioppo, W.B. Malarkey, and R. Glaser, �Acute

Psychological Stressors and Short-Term Immune Changes: What, Why, for Whom,

and to What Extent?� Psychosom Med (vol. 54:6,

1992) pp. 680-685.

10

J.K. Kiecolt-Glaser, R. Glaser, E.C. Shuttleworth, C.S. Dyer, P. Ogrocki,

and C.E. Speicher, �Chronic Stress and Immunity in Family Caregivers of

Alzheimer�s Disease Victims� in Psychosom Med

(vol. 49:5, 1987) pp. 523-535.

11

J.K. Kiecolt-Glaser, L.D. Fisher, P. Ogrocki, J.C. Stout, C.E. Speicher, and

R. Glaser, �Marital Quality, Marital Disruption, and Immune Function� in

Psychosom Med (vol. 49:1, 1987) pp. 13-34.

12

B.A. Esterling, J.K. Kiecolt-Glaser, and R. Glaser, �Psychosocial Modulation

of Cytokine-Induced Natural Killer Cell Activity in Older Adults� in

Psychosom Med (vol. 58:3, 1996) pp. 264-272.

13

J.K. Kiecolt-Glaser, W. Garner, C. Speicher, G.M. Penn, J. Holliday, and R.

Glaser, �Psychosocial Modifiers of Immunocompetence in Medical Students� in

Psychosom Med (vol. 46:1, 1984) pp. 7-14.

14

G.F. Solomon, �Physiological Responses to Environmental Design:

Understanding Psychoneuroimmunology (PNI) and Its Application for

Healthcare� in J. Health Des (vol. 8, 1996) pp.

79-83.

15

G.F. Solomon, �Whither Psychoneuroimmunology? A New Era of Immunology, of

Psychosomatic Medicine, and of Neuroscience� in Brain

Behav Immun (vol. 7:4, 1993) pp. 352-366.

16

G.F. Solomon and A.A. Amkraut, �Psychoneuroendocrinological Effects on the

Immune Response� in Annu Rev Microbiol (vol.

35, 1981) pp. 155-184.

17

G.F. Solomon and R.H. Moos, �Psychologic Aspects of Response to Treatment in

Rheumatoid Arthritis� in GP (vol. 32:6, 1965)

pp. 113-119.

18

R.H. Moos and G.F. Solomon, �Personality Correlates of the Degree of

Functional Incapacity of Patients with Physical Disease� in

J. Chronic Dis (vol. 18:10,

1965) pp. 1019-1038.

19

Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization, as adapted by

the International Health Conference, New York, 19-22 Jun 1946, signed on 22

Jul 1946 by the representatives of sixty-one states (Official

Records of the World Health Organization, no. 2, p. 100) and entered

into force on 7 Apr 1948.

20

E.L. Idler and S.V. Kasl, �Religion among Disabled and Nondisabled Persons

I: Cross-Sectional Patterns in Health Practices, Social Activities, and

Well-Being� in J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci

(vol. 52:6, 1997) S294-S305.

21

S. Ben Eliyahu, G.G. Page, R. Yirmiya, and G. Shakhar, �Evidence that Stress

and Surgical Interventions Promote Tumor Development by Suppressing Natural

Killer Cell Activity� in Int J Cancer (vol.

80:6, 1999) pp. 880-888.

22

S. Ben Eliyahu, R. Yirmiya, J.C. Liebeskind, A.N. Taylor, and R.P. Gale,

�Stress Increases Metastatic Spread of a Mammary Tumor in Rats: Evidence for

Mediation by the Immune System� in Brain Behav Immun

(vol. 5:2, 1991) pp. 193-205.

23

S. Ben Eliyahu, R. Yirmiya, Y. Shavit, and J.C. Liebeskind, �Stress-Induced

Suppression of Natural Killer Cell Cytotoxity in the Rat: A Naltrexone-Insensitive

Paradigm� in Behav Neurosci (vol. 104:1, 1990)

pp. 235-238.

24

G.F. Solomon, �Psychoneuroimmunology and Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Infection� in Psychiatr Med (vol. 7:2, 1989)

pp. 47-57.

25

S. Cohen, D.A. Tyrrell, and A.P. Smith, �Psychological Stress and

Susceptibility to the Common Cold� in N Engl J Med

(vol. 325: 9) pp. 606-612.

26

G.F. Solomon, �Emotions, Stress, the Central Nervous System, and Immunity�

in Ann NY Acad Sci (vol. 164:2, 1969) pp.

335-343.

27

P.T. Marucha, J.K. Kiecolt-Glaser, and M. Favagehi, �Mucosal Wound Healing

Is Impaired by Examination Stress� in Psychosom Med

(vol. 60:3, 1998) pp. 362-365.

28

M.S. Harbuz, �Chronic Inflammatory Stress� in

Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinal Metab (vol. 13:4, 1999) pp.

555-565.

29

G.F. Solomon, G.H. Ironson, and E.G. Balbin, �Psychoneuroimmunology and

HIV/AIDS� in Ann NY Acad Sci (vol. 917, 2000)

pp.500-504.

30

M. Irwin, �Immune Correlates of Depression� in Adv Exp

Med Biol (vol. 461:1) pp. 1-24.

31

S. Zisook, S.R. Shuchter, M. Irwin, D.F. Darko, P. Sledge, and K. Resovsky,

�Bereavement, Depression, and Immune Function� in

Psychiatry Res (vol. 52:1) pp. 1-10.

32

M. Irwin, T. Patterson, T.L. Smith, C. Caldwell, S.A. Brown, J.C. Gillin et

al., �Reduction of Immune Function in Life Stress and Depression� in

Biol Psychiatry (vol. 27:1, 1990) pp. 22-30.

33

S.R. Lindheim and M.V. Sauer, �Stress and Infertility: �The Chicken or the

Egg?�� in Fertil Steril (vol. 68:2, 1997) pp.

384-385.

34

M.M. Seibel, �Infertility: The Impact of Stress, the Benefit of Counseling�

in J Assist Reprod Genet (vol. 14:4, 1997) pp.

181-183.

35

L.R. Schover, �Recognizing the Stress of Infertility� in

Cleve Clin J Med (vol. 64:4, 1997) pp. 211-214.

36

H. Chiba, E. Mori, Y. Morioka, M. Kashiwaskura, T. Nadaoka, H. Saito et al.,

�Stress of Female Infertility: Relations to Length of Treatment� in

Gynecol Obstet Invest (vol. 43:3, 1997) pp.

171-177.

37

S.K. Wasser, G. Sewall, and M.R. Soules, �Psychosocial Stress as a Cause of

Infertility� in Fertil Steril (vol. 59:3, 1993)

pp. 685-689.

38

J. Shepherd, �Stress Management and Infertility� in

Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol (vol. 32:4, 1992) pp. 353-356.

39

M.W. Nortvedt, T. Riise, K.M. Nyland, and B.R. Hanestad, �Type I Interferons

and the Quality of Life of Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Results from a

Clinical Trial on Interferon Alfa-2a� in Mult Scler

(vol. 5, Oct 1999) pp. 317-322.

40

T. Vial and J. Descotes, �Clinical Toxicity of the Interferons� in

Drug Saf (vol. 10:2, Feb 1994) pp. 115-150.

SimpleToRemember.com - Judaism Online |